Opportunities to Rebuild Western North Carolina in the Face of Climate Catastrophe

About the author

Aspen Johnston is a graduate student pursuing a Master of Urban Design at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. This fall, the Urban Design Center awarded Aspen a year-long fellowship enabling them to work under the tutelage of practicing urban designers and city government. Drawing from a decade of living and working in Western North Carolina, their passion lies in building climate-resilient cities through preventative design. Utilizing their undergraduate degree in Sustainable Development, Aspen explores how communities can adapt and transform in response to climate-related challenges. Following the devastating events of September 27, 2024, Aspen finds hope and opportunities for renewal in the aftermath of this and other natural disasters.

Unprecedented and catastrophic, Hurricane Helene’s devastation brought Western North Carolina’s vulnerability to the national stage.

Western North Carolina, more specifically the city of Asheville, has long been viewed as a climate haven or climate destination. “Climate havens or climate destinations are situated in places that avoid the worst effects of natural disasters and have the infrastructure to support a larger population.” (CNBC). While this title has given residents and visitors a false sense of security, the city of Asheville has committed to mitigating and adapting to the effects of climate change. Following the destructive floods caused by Hurricane Frances and Ivan in 2004, the city of Asheville worked diligently to create stronger resiliency for the region. Using FEMA funds to purchase residential buildings located along the rivers, reworking river-adjacent parcels into parks and wetland restoration sites, and designing an adaptive spillway system for the North Fork Reservoir, local officials hoped their efforts would be enough to prevent future catastrophe and infrastructure failures. In recent years the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center (NEMAC) worked alongside the public and private sectors to create a Municipal Climate Resilience Plan (MPAC), officially released in 2023.

So, why wasn’t it enough? Climate-related natural disasters displaced more than three million Americans in 2023 (Urban Institute). This mass movement of climate refugees and the increased appeal of climate havens are creating new pressures—climate havens struggle to adapt their infrastructure and manage rising housing costs as populations quickly increase. The City of Asheville’s 2018 Climate Resilience Report noted, “A major challenge Asheville continues to face is the increasing risk of flooding due to more development and impervious surfaces.”

Many areas within Western North Carolina face higher flood risk due to the geographic limitations. Considering the historical tendency of lower-income, marginalized communities to settle alongside river banks in the valleys of large mountainous slopes, the story of Asheville and the surrounding region cannot be told without exploring the uphill battle faced as large volumes of water make their way downstream. Although the city of Asheville has been preparing for greater catastrophic flood risk as climate change becomes more severe, previous efforts were no match against the sheer force of Hurricane Helene. Asheville’s unique geography paired with aging and crumbling infrastructure became the region’s downfall as the storm destroyed road, water, cell, and electrical utilities as well as homes and stores. As residents sort through the muck, the rest of the nation must take time to think critically and reflect on how to prepare and respond to climate events that are not only more frequent but alarmingly more severe. This region has the opportunity to rebuild and invest in climate resiliency and smart growth. As U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg noted while visiting Western North Carolina following the storm, “The job now is to make sure the infrastructure being rebuilt is as resilient as the people impacted.”

Climate change makes navigating extreme weather conditions increasingly more common regardless of where you live. In the years leading up to Hurricane Helene, climate scientists across the state of North Carolina have urged local government leaders to develop plans that cater to climate resiliency, but too often the recommendations have yet to be implemented or have been outpaced by new development. The measures put in place to foster resilience were easily overpowered by the force of this storm system, bringing to light the areas that have needed further investments for years, if not decades.

Rebuilding “as resilient as the people impacted”, as Buttigieg recommended, is only possible if the impacted are given a voice during the rebuilding process. As a community struggling with the pressures of new, often wealthy, climate refugees, the most critical component for planning the future of Western North Carolina is ensuring a diverse range of community involvement in every step of the planning process. Close community collaborations create a cohesive environment that fosters trust between individuals and government officials. Thoughtful planning of resilient design projects provides these communities with the opportunity to play a role in deciding the future of their homes, creating spaces they will actually use, value, and benefit from.

According to the American Flood Coalition, community engagement is vital for creating flood resilience because it prompts “greater dialogue about flooding and what it means to residents. [Community engagement] generates innovative ideas to build flood resilience into everyday spaces like parks, and leads to greater community buy-in and support for projects.” Each of the locations mentioned below has done a remarkable job at engaging with, uplifting, and empowering their community. To design thoughtfully with community needs at the forefront of redevelopment, government agencies must work alongside community-based organizations, local stakeholders, neighborhood associations, and volunteer-led groups. We can look to and learn from examples down the road and across the world.

In North Carolina, the City of Kinston partnered with Kinston Teens and the American Flood Coalition to reimagine a seven-acre park just north of their downtown region. Redesigning their park aims to better manage extreme weather events, and create a usable, cohesive community space. The park design was successful and well supported because the parks and recreation team incorporated community input throughout the planning stages. Kinston’s planners did this by organizing equitable and accessible community input events through various outreach methods, creating opportunities for residents to share memories of the project and how flooding has affected them, providing updates to community members while creating new plans, and thoughtfully incorporating input into the final master plan.

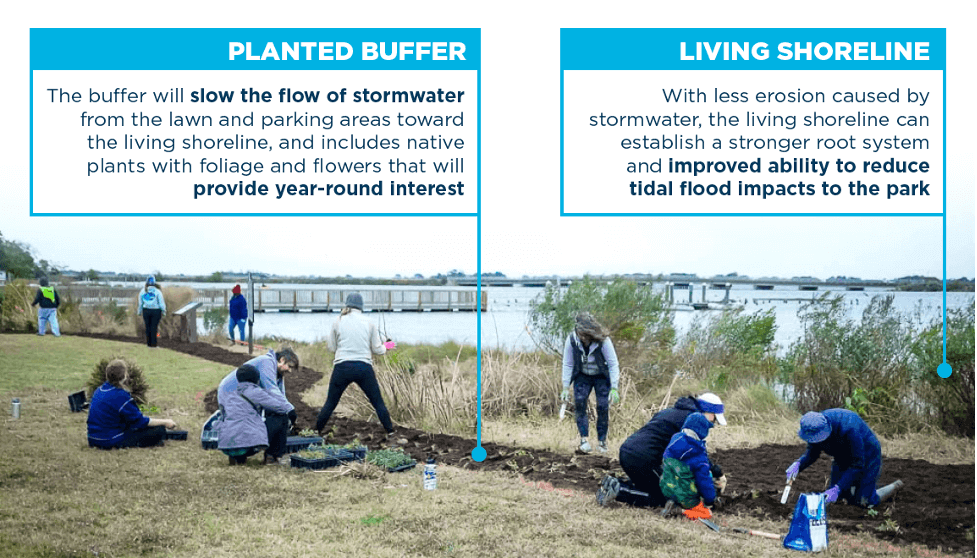

Meanwhile, in the City of Hampton, Virginia, the American Flood Coalition and Partnership for a New Phoebus worked together to actively engage community members to find low-cost, effective solutions to build flood resiliency. For Hampton, this took shape in the form of reimagining an existing Adopt-A-Spot Program to focus more heavily on flood mitigation. By organizing volunteer workdays, the Phoebus Neighborhood was able to strengthen living shorelines with new plants and landscaping. Intentional planting provides more biodiversity and reduces erosion and flood risk.

An inspiring project in the Dar es Salaam Region of Tanzania takes place on a much larger scale, with a bigger budget, raising the scope of engagement and impact for the adjacent communities. The Msimbazi Basin Development Project aims to, “transform risk zones into opportunity zones” by converting the flood-prone Msimbazi River basin into a park. With surrounding mixed-use developments, the government aims to bring economic benefits and mobility to the surrounding area, uplifting the community as a whole. The Tanzanian government achieved this with careful environmental and social assessments, providing the necessary data for determining which areas are most in need of support and where relocation efforts are necessary. By keeping the local community involved and educated through every step of the process, planning officials understand the interests and needs of the public. This has led to the “Resettlement Action Plan and Livelihood Restoration Plan,” creating an official pathway to benefit those residing in flood-prone areas while creating the space for the bold project to be implemented.

The rebuilding of Western North Carolina will be an uphill battle, both literally and figuratively. We must act quickly but wisely to avoid the fate of Sisyphus in which we are constantly having to rebuild in response to climate disasters exacerbated by climate change and poor planning. We must reimagine the way we shape our environment, from road construction to floodplain development. The work of redesigning the future of Western North Carolina needs to emphasize creating a sustainable, affordable place for all who wish to reside there.

Government authorities must rewrite zoning laws to be more intentional with hillside construction and promote denser development in stable areas. These create a less car-dependent community, especially for those living in remote areas. Bridges may need to be reinforced and built higher than previously thought. Reservoirs and dams must be evaluated with a critical eye to prepare for intense flooding events in the future. Substantial implementation of green infrastructure will be another important trend to work towards as we reimagine the future for Western North Carolina and beyond. Converting our riverbanks to carefully planned riparian zones and well-connected greenways are valuable nature-based solutions to implement. The methods listed above are just a few stepping stones to create the climate-resilient cities our future generations need.

As Western North Carolina looks to recover, attempting to rebuild the outdated status quo would be foolish. Learning from Kinston, Hampton, and Tanzania, North Carolina leaders need to anticipate the climate impacts of the future and design infrastructure to withstand such devastating events, all while highlighting the needs of individual communities. Connecting with local advocacy groups and putting pressure on our government officials allows us as individuals to play a role in urging those in power to expedite the implementation of resilient strategies. By doing so, we can ensure our communities can move forward and rebuild with care, intention, and an innovative approach to reimagining what is possible.

Read more about Community-Driven Climate Resilience Planning here.

To learn more about Aspen and the Urban Design Center, check out our Instagram.