Written by Jen Baehr – Charlotte Historic Preservation

Honoring Charlotte’s Historic Landmarks

Every year in May, local historic preservation groups, historical societies, businesses, and civic organizations across the country celebrate Preservation Month. This year’s theme, “Harnessing the Power of Place,” recognizes the many ways that preservation work strengthens communities, revitalizes neighborhoods, supports sustainability, and connects us through shared history. The Charlotte Historic District Commission (HDC) celebrated this year’s theme by showcasing some of the City’s 45 locally designated landmarks located in Charlotte’s local historic districts. Throughout the month of May, the HDC highlighted these landmarks with a series of social media posts on the Charlotte Planning, Design, and Development Department’s Instagram page (@cltplanning). The local landmarks featured include a variety of property types, such as a cemetery, school, single-family houses, apartments, commercial buildings, and monuments. This blog post expands on the Instagram posts by sharing more in-depth stories of the people and events that make each of these local landmarks special and significant to the City’s history. The following information has been gathered from the extensive work of historian Dr. Tom Hanchett and the landmark designation reports on file with the Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

McCrorey Heights

Charlotte’s newest local historic district, McCrorey Heights was designated in 2022. McCrorey Heights is important to the City’s history as it was home to many leaders of the Civil Rights movement not only in Charlotte but across the nation. The homes of Dr. Robert H. Greene and Dr. Reginald A. Hawkins are designated as local landmarks and represent the legacy of two of Charlotte’s most influential African American leaders. The Dr. Robert H. Green House, located at 2001 Oaklawn Avenue was built in 1936 and designated as a local landmark in 2009. The Colonial Revival style home is well-preserved and is one of the few surviving pre-World War II examples of this style associated with the African American community in Charlotte. Dr. Greene was a respected doctor not only in Charlotte but statewide. He set up his own medical practice on Brevard Street in the Brooklyn neighborhood in Uptown. While he was running his own practice, Dr. Greene was also the staff physician at Good Samaritan Hospital (now the site of the Bank of America Stadium). His Civil Rights activism included taking part in the successful lawsuit filed in 1951 to desegregate the golf course at Revolution Park. This case was widely followed across the United States and helped invalidate the deed covenants that prohibited African Americans from public parks.

The Dr. Reginald A. Hawkins House located at 1703 Madison Avenue was the built in 1953 and designated as local landmark in 2019. In addition to being the home where Dr. Hawkins lived with his wife and children, the house functioned as the command center for Dr. Hawkins’ activities during his two decades of Civil Rights work. Dr. Hawkins was one of Charlotte’s most prominent and tireless activists during the Civil Rights movement. He played a central role in the integration of Charlotte schools, hospitals, the airport and more. One of Dr. Hawkins’ greatest efforts was his role in the series of actions that culminated in the landmark Swann v Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court case that brought court-ordered busing to the nation. Targeted in the 1965 bombings of Civil Rights leaders’ homes, Dr. Hawkins’ house serves as a powerful symbol of resilience in the face of violence and hate.

Fourth Ward

Designated in 1976, Charlotte’s first local historic district, Fourth Ward is home to many of Charlotte’s oldest and most significant places. Settler’s Cemetery, located at 200 W. Trade Street was designated in 1984 as a local landmark given its significance as the first municipal cemetery in Charlotte and as the resting place for many members of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County’s founding families, enslaved persons, industrialists, entrepreneurs and soldiers. The cemetery was established in the 1760s and operated as the City’s main cemetery until the 1860s when Elmwood Cemetery opened. Nestled among churches and skyscrapers, this hilltop cemetery serves as a peaceful park-like space for residents, visitors and workers in Uptown.

The Crowell-Berryhill Store, now Alexander Michael’s Restaurant and Tavern, was built in the 1890s and designated as a local landmark in 1982. This corner store located at 401 W. 9th Street, has served many uses over the years including a grocery, laundry and auto body shop. The building is the only turn of the century grocery store which survives in Uptown. During the mid-1970s the building fell into disrepair and was in danger of being demolished, but fortunately was preserved and underwent major renovations to bring it back to its original appearance. The Crowell-Berryhill Store is an excellent example of sensitive adaptive reuse, showing how the past can be preserved while serving the present.

Plaza Midwood

The vibrant and eclectic Plaza-Midwood local historic district was designated in 1992. The Bishop John C. Kilgo House and VanLandingham Estate stand out as some of the most architecturally significant properties in the District. The Bishop John C. Kilgo House at 2100 The Plaza was built in 1915 and designated a local landmark in 2008. The residence, designed by notable Charlotte architect Louis H. Asbury, blends the Colonial Revival and Craftsman architectural styles with a balanced hip roof, front porch supported by Tuscan columns with brackets, and deep eaves with exposed rafter tails. The Kilgo House was one of the first homes built in Chatham Estates (now Plaza Midwood) and its first owner Bishop John C. Kilgo was a Methodist minister and the president of Trinity College (now Duke University). The property once had enslaved quarters that have since been demolished. Though it has evolved over the years, this well-preserved landmark remains a unique architectural gem in the Plaza Midwood neighborhood.

The VanLandingham Estate, just across the street from the Kilgo House, at the corner of The Plaza and Belvedere Avenue was built in 1913 and designated a local landmark in 1977. The estate house was designed by prominent local architects Charles Christian Hook and William G. Rogers in the Californian Bungalow style, which was popular at the time the home was built. The large two-story house is a rare local example of the bungalow style adapted to massive proportions, a departure from the style’s simple origins. The estate is famous for its expansive gardens, known to be one of the most noteworthy in Charlotte.

Dilworth

The largest of the City’s local historic districts, Dilworth was developed as Charlotte’s first suburb and was connected to the Uptown area by Charlotte’s first electric streetcar. The Dilworth neighborhood is characterized by its curved roads, mature tree canopy, and diversity of architectural styles. The local landmarks known as the City House and Myrtle Square Apartments reflect how housing evolved to fit the needs of the growing City during the first half of the 20th century. The City House at 500 E. Kingston Avenue was built in 1909 and was designated as a local landmark in 2006. The City House is one of the oldest residences in Charlotte, which was originally designed as a duplex. The City House name comes from prominent Charlotte architect Charles C. Hook, who encouraged the building of adjoining residences, which he referred to as “city houses”. Some of the City House’s earliest residents included teachers, dressmakers, and factory workers. Though the building was divided into several apartments over time, in the 1980s it was restored to its original appearance, for which the owners received an award from the Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

The Myrtle Square Apartments at 1121 Myrtle Avenue were built in 1939 and designated a local landmark in 2007. The apartments are a rare local example of the unique Art Moderne architectural style, featuring glass block, porthole windows, decorative iron work, and clean geometric lines. The layout of the complex serves as one of the most sophisticated examples of the garden court multi-family housing type in Charlotte. The garden court community is an urban planning concept that preserves open green space by concentrating housing into large multi-family complexes called “super blocks” which were integrated with the natural environment. The garden court movement gained popularity in Europe due to the need for housing that arose from the destruction of World War I and the rapid effects of industrialization. The Myrtle Square Apartments reflect how Charlotte was transforming during the 20th century due to the City’s rapid expansion caused by the textile industry. This led to unprecedented population growth, creating the need for multi-family housing, a trend we still see today across the City.

Hermitage Court

Tucked within the Myers Park neighborhood is Hermitage Court, the smallest of Charlotte’s local historic districts with approximately 36 properties, two of which are locally designated landmarks, the Simmons House and the Hermitage Court Gateways. The Simmons House, 625 Hermitage Court, was designated a local landmark in 2021. Constructed in 1913, the house is one of the oldest in Myers Park, one of the first planned suburban developments outside of Charlotte at the time. The home represents one of the most significant examples of Neoclassical Revival architecture in the City, featuring a symmetrical façade, full-height portico supported by Ionic columns, and classical ornamentation. The home was built for prominent attorney and developer, Floyd Macon Simmons for $12,000. The Simmons House has evolved over the years with additions and alterations but many of its original architectural features remain, a testament to the great workmanship and care that went into its construction.

The Hermitage Court Gateways, located at the east and west entrances to Hermitage Court were built in 1912 and designated as a local landmark in 1981. Inspired by the entrance to President Andrew Jackson’s home in Nashville, the gateways were built with granite and red mortar by Scottish stonemasons. The gateways were intended to set the tone and character of the new stately development.

Wesley Heights

Designated as a local historic district in 1994, Wesley Heights is an early 20th century streetcar suburb that contains mostly brick and frame bungalow style homes, which is why the Calvin Neal and Wadsworth Houses stand out in this neighborhood. The Calvin Neal House at 612 & 614 Walnut Avenue was built in 1927 and designated as a local landmark in 2003 because of its unique use of stone on almost the entire exterior of the home. The Neal House, likely constructed from stock building plans, reflects how homeowners during the post-World War I housing boom found ways to personalize their homes. Advances in construction methods during the late 19th and early 20th centuries made building materials like wood, glass, and brick more affordable and widely available. Stone was seen as a costly and lavish building material that was reserved for grand civic and commercial buildings, but rarely used for residential buildings, making the Neal House an unusual example of this type of construction.

Designated as a local landmark in 1994, the Wadsworth House, 400 S. Summit Avenue, was built in 1911 and is one of the earliest homes in Wesley Heights. The house breaks with the surrounding homogeneity of the area because of the large size of the property, the way the house sits back off the street on a hilltop and its sophisticated, grand stature amongst the quiet bungalows in the Wesley Heights neighborhood. The original servant quarters/carriage house remains behind the house, a rare building type to survive in Charlotte. The large, two-and-half-story Arts and Crafts style house was originally home to George Pierce Wadsworth, a pioneer of Charlotte’s streetcar and livestock industries. The Wadsworth House was also home to Judge Shirley Fulton, the first African American female prosecutor in Mecklenburg County and the first African American woman on the Superior Court bench in North Carolina. Judge Fulton was an important community leader, playing an instrumental role in helping designate the Wesley Heights neighborhood as a local historic district. The current owners of the home completed an extensive restoration project in 2021 for which they received an award from the Charlotte Museum of History.

Wilmore

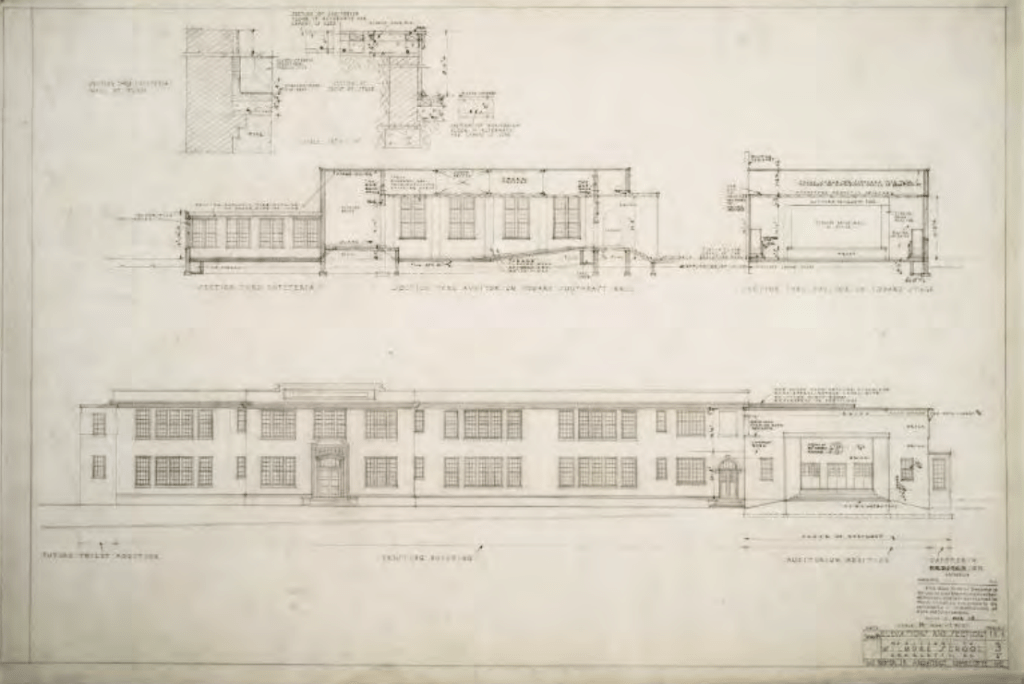

Designated as a local historic district in 2010, Wilmore was built on farmland around the Rudisill Gold Mine, which drove the United States’ first gold rush around Charlotte in the mid-19th century. Today, Wilmore is mainly a single-family neighborhood but also contains duplexes, apartments, institutional and commercial buildings. Designated in 2018, the Wilmore Elementary School is the only local landmark in the Wilmore neighborhood and is a lasting symbol of the neighborhood’s story. As a response to the growing working-class neighborhood, the Wilmore Elementary School opened in 1925 and was the only school to ever be built in Wilmore. The school was designed by well-known local architect Louis H. Asbury and underwent several expansions and renovations, reflecting the evolving needs of the community. In 1970, the Wilmore Elementary School was desegregated as a result of the landmark Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Supreme Court case. Though the school closed in 1978, its story isn’t over, plans are underway to redevelop the site which will incorporate the school as part of a mixed-used development, ensuring the school’s legacy continues in a new way. The preservation of the Wilmore Elementary School was made possible through the work of Preservation North Carolina, a statewide non-profit that aims to find new uses for historic buildings threatened with demolition.

Oaklawn Park

One of Charlotte’s newest local historic districts designated in December 2020, Oaklawn Park holds deep roots in the City’s Civil Rights, education and cultural history. Although Oaklawn Park does not have any locally designated landmarks currently, the homes of Reverand Calvin and Anna Hood, Dr. Mary T. Harper, and Dr. C.W. Williams are worthy of potential landmark status given their association with these important community leaders.

Rev. Calvin and Anna Hood purchased their home at 1327 Orvis Street in 1957 with a GI mortgage, federal funding that helped many veterans purchase homes after World War II. The Hoods were able to work with the original Oaklawn Park developer, the Ervin Company, to pick the interior finishes, paint colors, window treatments and more. Rev. Hood was a professor at Johnson C. Smith University and was a leading voice in Charlotte’s Civil Rights movement, marching in Selma and fighting for integration in local hospitals and restaurants. His wife, Anna Hood was a true trailblazer herself; being the first person of color hired at Charlotte’s Social Security office, co-founder and past president of the Charlotte Club of the National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women’s Clubs Inc., and a civic leader who helped pave the way for African American women in government.

Dr. Mary T. Harper, lived in the house at 1323 Dean Street. As one of the first African American professors at UNC Charlotte, Dr. Harper also was responsible for developing the African American Studies program at University. Her leadership extended beyond the University into the community as a co-founder of the Harvey Gantt Center for African American Art and Culture. Dr. Harper purchased the home on Dean Street when it was first built and lived there until 2020.

Though he lived in the home at 1418 Russell Avenue briefly, the home represents a key chapter in the life of Dr. C. W. Williams, one of Charlotte’s most influential medical leaders. Dr. Williams was the first African American physician to practice at Charlotte Memorial Hospital (now Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center) and a pioneer in bringing healthcare clinics to underserved communities. Dr. Williams moved from his home in Oaklawn Park to a larger home in the suburban upper-middle class Hyde Park neighborhood, which he co-developed along with physician Dr. Walter Washington. Dr. Williams legacy lives on today at the C.W. Williams Community Health Center, which he established in 1981.

As reflected in the landmarks included in this post, Charlotte’s history is rich, and these places are important to honor and celebrate. Through the stewardship of the homeowners and important work of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmark Commission and Charlotte’s Historic District Commission these places live on to tell the stories of some of the most influential Charlotteans. For more information on local historic districts and local landmarks please contact the Charlotte Historic District Commission at charlottehdc@charlottenc.gov.